UCI Bans Carbon Monoxide Rebreathing – But Is It Gone for Good?

As of February 10, 2025, the latest UCI substance ban has taken effect, this time targeting carbon monoxide (CO) rebreathing—a practice that has gained traction in recent years. Like many regulatory decisions in professional cycling, the move has sparked debate. While some question its potential harm, others see it as a significant risk. But with its official ban, is this truly the end of CO rebreathing?

What Is Carbon Monoxide Rebreathing, and Why Was It Used?

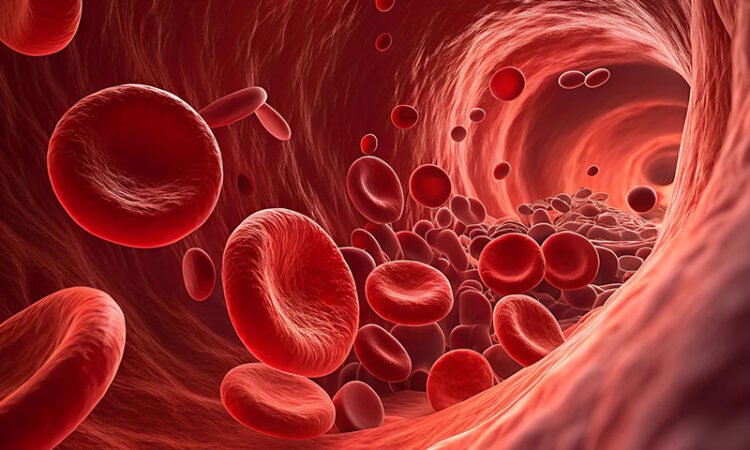

As the name suggests, carbon monoxide rebreathing involves controlled inhalation of CO. Before administration, baseline levels of CO in an athlete’s breath and blood are measured. The athlete then inhales a precise amount of CO mixed with oxygen through a rebreathing device for two minutes. This CO binds with haemoglobin in red blood cells to form carboxyhaemoglobin, after which follow-up tests assess changes in key blood metrics, including haemoglobin mass (Hb).

For years, teams have used this method as a data-gathering tool to assess the impact of altitude training on their athletes. When training at altitude, where oxygen levels are lower, the body adapts by increasing red blood cell production to enhance oxygen transport. Upon returning to lower altitudes, this adaptation leads to improvements in VO2 max and lactic acid tolerance.

Haemoglobin mass is directly linked to VO2 max—the greater the Hb mass, the more oxygen an athlete can transport, and the better their endurance. Traditional methods of measuring altitude adaptation, such as full blood counts, have limitations. An increase in blood volume without a corresponding rise in haemoglobin can lower hematocrit levels, making it an unreliable marker. CO rebreathing offers a direct measurement of total haemoglobin mass, eliminating this issue.

Dr. David De Klerk of UAE Team Emirates explains it succinctly:

“If you could take all the haemoglobin in your body, put it on a scale, and weigh it, that would be the best way of measuring it—and that’s essentially what carbon monoxide rebreathing does.”

With its ability to accurately track haemoglobin changes, CO rebreathing has also been explored in assessing the benefits of heat training, which research suggests can boost Hb mass in a manner similar to altitude training.

The Controversy – Data Collection or Performance Enhancement?

On the surface, CO rebreathing appears to be a sophisticated monitoring tool, no different from using a power meter to track training progress. However, the controversy arises from evidence suggesting it could be leveraged as a performance-enhancing method in its own right.

Investigations by The Escape Collective highlighted concerns that CO inhalation protocols could not only measure the effects of altitude training but also mimic them. Regular CO exposure triggers a hypoxic response in the body, stimulating an increase in haemoglobin levels—just as high-altitude training does.

Two notable studies underscore this risk:

- A 2019 study found that participants who inhaled CO before treadmill sessions five times a week for a month showed greater increases in Hb mass and VO2 max than those training without CO exposure.

- A 2021 study on amateur cyclists revealed that those who inhaled a controlled CO dose five times a day for three weeks saw a 4.8% increase in haemoglobin mass and VO2 max.

Given the history of athletes and teams seeking every possible advantage, concerns mounted that CO rebreathing could be exploited. The UCI’s decision to ban it wasn’t driven solely by potential long-term health risks but rather by a fundamental principle: any artificial manipulation that alters blood composition is prohibited under its regulations.

What Comes Next?

Under the new ruling, the UCI has authorized a single, medically supervised CO inhalation for haemoglobin mass measurement, with a second session permitted only after a two-week interval. Yet, despite ongoing discussions, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has yet to take an official stance on the issue.

With no outright global ban, teams that have already incorporated CO rebreathing into their training may still find ways to work within (or around) these restrictions. The lingering regulatory gap raises concerns about potential loopholes and the possibility of quiet, continued use.

While the UCI’s decision marks a step toward controlling its application, it’s unlikely to be the last we hear of CO rebreathing—and the debates surrounding its role in elite cycling